Borderline Personality Disorder: Beyond the Label

One of the biggest critiques of diagnostic systems is that the labels carry with them perceptions and understandings that are stigmatic. You are more than a singular label.

By Jessica Young, Featured Writer.

As someone working within the mental health field, borderline personality disorder (BPD), is a label that is frequently encountered. However, it is one that is often misunderstood and burdened with misconceptions.

Diagnosis can be a controversial issue; one that can be experienced very differently by individuals receiving labels, and one debated amongst professionals within clinical practise and research. For example, Szasz (1960) outlined the extremity of the argument against using labels through his paper ‘Myth of Mental Illness’, suggesting that utilising labels and medicalising ‘everyday suffering’ (e.g. sadness, worry), can exacerbate mental health within society. Moreover for those labelled, it may add weight to an already heavy challenge by introducing stigma, social scrutiny, and generalisations into an individual’s life that may undermine, illegitimatize or victimise their individual experience and feeling of belonging in society. Though it should be acknowledged that diagnosis can provide a framework for validating, understanding, treating, and managing experiences of distress or disorder.

No matter one’s view (and whether you’re working with those experiencing mental health crises, or dealing with it yourself), labels are something we all encounter and have to deal with. Whilst we may feel more familiar with labels such as anxiety or depression (perhaps because of their higher prevalence rate or increased media presence), there are other conditions such as borderline personality disorder, that may be less familiar and this calls for greater recognition and understanding.

What is BPD, the Label?

BPD features in the DSM 5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), one of the most prominent sources for mental health diagnosis as produced by the APA (American Psychiatry Association).

In obtaining a label of BPD, individuals have to present five or more of the following criteria over a prolonged period, in a manner disruptive to their daily lives (Very Well Mind, 2020):

Diagnosis can ignite a confusing cycle. Symptoms attract labels, such labels are used to justify or explain the experience of these symptoms. The chicken and the egg. Diagnostic criteria are not aetiological, if someone is presenting you with their label, is this how they wish to characterise their own experiences?

Stigma & Misconceptions

One of the biggest critiques of diagnostic systems is that the labels carry with them perceptions and understandings that are stigmatic.

You are more than a singular label.

Labelling exists for various reasons and it is directive in pinpointing suitable avenues for treatment and symptom management. Nevertheless, it is this very directive nature that can cause people with labels such as BPD, to experience prejudice and discrimination from those around them due to the stigma associated with such a label.

We all possess prejudices and have the propensity to stereotype those around us. It is part of our cognitive interpretation of the world and is known as a process called ‘Othering’. In other words, making judgements and having preconceptions about things or other people does not necessarily make you a bad person and is in fact argued to be an evolutionary protective response to a generalised “unknown” group or type of individual with certain traits or characteristics (Norriss 2011; Understanding Prejudice, 2002). It only becomes “bad”, if you are to act on that prejudice, where it would then become discrimination.

Research using an in-depth qualitative approach, has highlighted how the processes of prejudice and behaviours of discrimination can have a negative impact at an individual level, highlighted by Sokratis et al (2004). Despite a smaller sized sample, detailed and in-depth accounts of individual’s experiences were obtained; stigma was an overarching worry for most participants, and those with personality disorders disclosed experiences of patronisation. Thus, it is inferable that prejudice possesses the ability to have a negative impact upon individual’s whom carry a personality disorder label, through negative experiences such as patronisation.

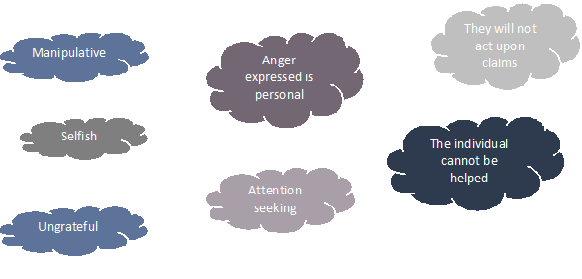

Focusing on BPD, the behaviours and manifestations associated with experiencing this mental health struggle can lend themselves to being misconstrued and are prone to stigmatic interpretation…

For example, someone experiencing BPD may be intensely fearful of being abandoned by those that work to support them; furthermore, they are prone to displaying anger towards the world. Consequently as someone supporting, you may find yourself on the receiving end of great frustration, stemming from the view that you are likely to abandon them/not uphold your role. Your interpretation of this reaction is key. You may view this as ungrateful or maybe even rude (stigma: this person is so ungrateful, I feel angry that my efforts are not being received, they cannot be helped).

At this point you may feel as if you want to withdraw your support or perhaps you begin to pay less attention to them, as opposed to what you originally were. You may become desensitised to their negative experiences. But, at this point you are confirming their fears and feeding their anger.

Working with & Supporting Someone with BPD

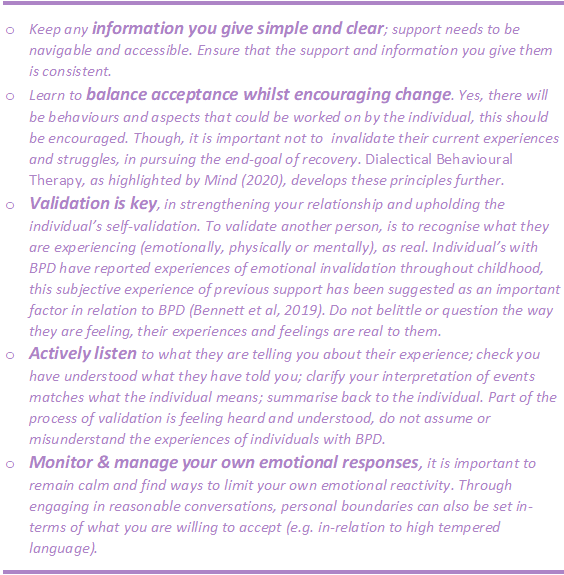

Whether you are working within a professional field or supporting a loved one, the absolute fundamental element of working with BPD is to maintain your empathy. Understand that a lot of the negative behaviours or reactions presented are not necessarily aimed at you; do not take this personally. Although, it is important to ensure that healthy boundaries are maintained (do not sacrifice your own comfort and wellbeing trying to help someone else), this does not have to be done so in a hostile manner. There are effective steps that can be taken to ensure the support you are providing remains the most helpful for the person receiving, and still balances your own wellbeing:

(The Royal College of Australian & New Zealand Psychiatrists, 2020)

Currently there is a considerable amount of uncertainty surrounding the understanding and conceptualisation of BPD, research still has a long way to go. As a criterion, BPD can be misdiagnosed and misinterpreted and therefore it makes it harder to obtain reliable and valid data for inferences to be made from research. Despite the need for further research and understanding, individual’s live with their symptoms and mental health experiences everyday - no matter the label, we should work to validate and support them.

Navigating misconceptions of BPD and learning how best to support individuals is but one component of the overarching debate relating to the use of labels, stigma, and the consequences of such. BPD as a mental health condition is relatively less understood than other labels such as depression and anxiety, perhaps with greater research, more knowledge will be available so to educate and combat the misconceptions. It is important that we are aware of the prejudices that surround experiences of BPD, working with and supporting individuals requires us to be vigilant as to when our own thoughts and actions are being biased in this way. Through greater awareness and understanding, we can work towards providing the most helpful support to those that need it; working towards recovery and remission.

References

Bennett, C., Melvin, A, G., Quek, J., Saeedi, N., Gordon, S, M., Newman, K, L. (2019), ‘Perceived Invalidation in Adolescent Borderline Personality Disorder: An Investigation of Parallel Reports of Caregiver Responses to Negative Emotions’, Child Psychiatry & Human Development, vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 209-221 [Online]. Available at https://link-springer-com.libezproxy.open.ac.uk/article/10.1007/s10578-018-0833-5 (Accessed 12th October 2020).

Mind (2020), ‘Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT)’ [Online]. Available at https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/drugs-and-treatments/talking-therapy-and-counselling/dialectical-behaviour-therapy-dbt/ (Accessed 2nd September 2020).

Norriss. J, 2011. ‘Othering 101: What Is “Othering”? There Are No Others.’ Available at https://therearenoothers.wordpress.com/2011/12/28/othering-101-what-is-othering/ (Accessed 2nd October 2020).

Sokratis, D., Stevens, S., Serfaty, M., Weich, S., King, M. (2004), ‘Stigma: the feelings and experiences of 46 people with mental illness: Qualitative study’. The British Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 184, no. 2, pp. 176-181 [Online]. Available at https://www-cambridge-org.libezproxy.open.ac.uk/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/920C7C5C3CC746B6C0562F7EC315C238/S0007125000229401a.pdf/stigma_the_feelings_and_experiences_of_46_people_with_mental_illness.pdf (Accessed 12th October 2020).

Szasz, T. (1960), ‘The Myth of Mental Illness’. American Psychologist, vol. 15, pp. 113-118 [Online]. Available at http://depts.washington.edu/psychres/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/100-Papers-in-Clinical-Psychiatry-Conceptual-issues-in-psychiatry-The-Myth-of-Mental-Illness.pdf (accessed 12th October 2020).

The Royal College of Australian and New Zealand Psychiatrists (2020), ‘Borderline personality disorder: Helping someone with borderline personality disorder’ [Online}. Available at https://www.yourhealthinmind.org/mental-illnesses-disorders/bpd/helping-someone (Accessed 14th October 2020).

Understanding Prejudice, (2002), ‘The Psychology of Prejudice: An Overview. Linking Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Discrimination’. London, Understanding Prejudice. Available at http://www.understandingprejudice.org/apa/english/page2.htm (Accessed 2nd October 2020).

Verywell mind (2020), ‘Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) Criteria for Diagnosis’ [Online]. Available at https://www.verywellmind.com/borderline-personality-disorder-diagnosis-425174 (Accessed 5th September 2020).